Alan Marshall, Chair of the Association of European Printing Museums

Of ships and sails and biscuit tins…

“The time has come, the Walrus said, to talk of many things: of shoes and ships and sealing-wax, of cabbages and kings, and why the sea is boiling hot and whether pigs have wings.”

Lewis Carroll

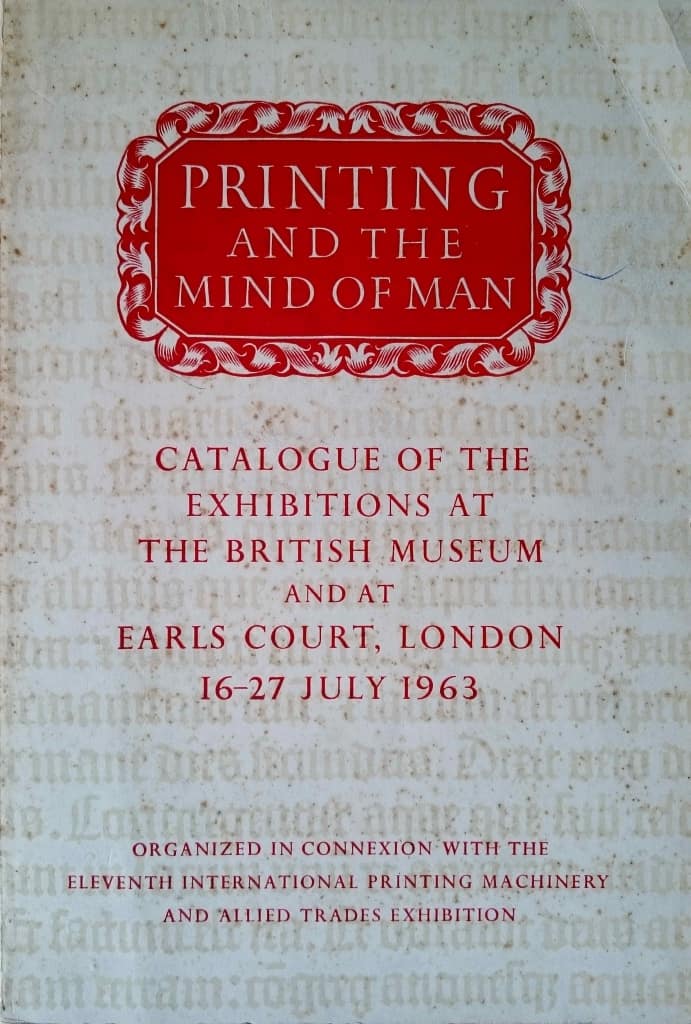

In 1963, a landmark exhibition on the history of printing and the book entitled Printing and the mind of man was held in London on the occasion of the eleventh International printing machinery and allied trades exhibition (IPEX). Organised on two different sites, the IPEX trade fair at the Earls Court Exhibition Centre and the British Museum, its aim was to provide an overview of five hundred years of printing, and of its impact on the development of civilization. It was probably the last major example of the nineteenth century tradition of international exhibitions which regularly exhibited the finest historical examples of printing alongside the most recent advances in contemporary graphic arts techniques.

In the fifty years which have elapsed since Printing and the mind of man, printing trade exhibitions have largely abandoned broader cultural and historical considerations, no doubt in order to better keep up with the successive waves of technological innovation which have profoundly altered the face of the graphic industries and the economic conditions under which they pursue their activities. During the same half-century exhibitions devoted to printing and graphic communication have become increasingly numerous and diversified, a tendency which has been reflected in the many printing museums which have been created during the same period. (The AEPM census of printing museums lists 140-odd new museums set up since the early 1970s.) However, despite the undeniable success of printing and related museums over the last half-century and the new approaches to print culture which have been developed, many important aspects of industrial printing in the twentieth century remain largely overlooked.

In the fifty years which have elapsed since Printing and the mind of man, printing trade exhibitions have largely abandoned broader cultural and historical considerations, no doubt in order to better keep up with the successive waves of technological innovation which have profoundly altered the face of the graphic industries and the economic conditions under which they pursue their activities. During the same half-century exhibitions devoted to printing and graphic communication have become increasingly numerous and diversified, a tendency which has been reflected in the many printing museums which have been created during the same period. (The AEPM census of printing museums lists 140-odd new museums set up since the early 1970s.) However, despite the undeniable success of printing and related museums over the last half-century and the new approaches to print culture which have been developed, many important aspects of industrial printing in the twentieth century remain largely overlooked.

Tin-printing, for example, has remained under the radar of printing museums. Exhibitions devoted to the subject are few and far between, and few printing museums have significant collections of tin-printing.

Since the late nineteenth century tin-printing – whose products include innumerable packaging applications, advertising panels, kitchenware and toys – has been a major sector of graphic production. Though greatly appreciated by collectors, some of whom are extremely knowledgeable on the subject, printing on metal, like printing on other non-paper substrates, hardly even merits a footnote in general histories of printing. Histories of graphic design, which are usually focused on the twentieth century, are more likely to mention it, but only from a visual point of view without ever situating it within the overall development of printing since the last quarter of the nineteenth century. And for book history, tin-printing it is one of the many major sectors of graphic production which are de facto considered to have had little or no impact on the technical and economic development of printing, despite the fact that packaging (of which tin-printing is but a part) became the mainstream of graphic production sometime in the first half of the twentieth century and that tin-printing was at the origin of one of the twentieth century’s leading industrial printing processes: offset lithography.

There were of course exceptions to this general climate of indifference. In 1971, for example, the Victoria and Albert Museum in London put on an exhibition entitled Season’s greetings: an exhibition of British biscuit tins 1868-1939.[1] Needless to say it did not have the same impact as Printing and the mind of man, and in the end its significance lay as much in what it said about the overlooked areas of printing history as it for what it actually displayed.

There are reasons why tin-printing has been largely overlooked by printing historians. One of the results of printing and book historians’ traditional tropism with ‘nobler’ products of the printing industry such as books, newspapers and periodicals is that the early development of tin-printing has remained rather obscure since its origins in the middle of the nineteenth century. All the more so since historians were not accustomed to dealing with the very considerable problems which printing on non-paper substrates raised. In order to be able to print on tinplate, printers had to solve the problems involved in establishing a uniform contact between a hard, more or less rigid substrate and the equally hard and unyielding surfaces of lithographic stones, printing metal or woodblocks. They also had to develop inks which would adhere to and remain permanent on the non-absorbent surface of tinplate. A further problem was that tin-printing had been largely incorporated into the metal box making industry, far from the inquisitive eyes of most printing historians.

Today, packaging remains very much a minority interest among printing historians and museums. Historical studies of the subject are few and far between and the AEPM’s census of printing and related museums includes only two packaging museums. The London-based Museum of Packaging and Advertising was created by the consumer historian Robert Opie in 1984 and has gone from strength to strength ever since. After its third move to larger premises in 2015 it now operates as the Museum of Brands, Packaging and Advertising. The Deutsches Verpackungsmuseum, which opened in 1997 in Heidelberg (Germany), maintains close links with the packaging industry and organises an annual packaging conference and award.

With the growing popularity of graphic design history and the increased visibility of printed ephemera in recent years, subjects which were once the more or less exclusive domain of collectors have begun to find a place in historians’ research agendas, but a great deal remains to be done to extend the historiography of printing in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. In the early 1970s the pioneer historian of packaging, Alec Davis [2], commented that ‘…academic writers on printing usually dealt with the bookish side of the industry rather than its lowly sides concerned, like tin-printing, with packaging and homely domestic wares. Printing and the mind of man is a much nobler concept than Printing and the stomach of man, but they both have a history’.[3] The need to underline – and undermine – historians’ fixation with the most culturally prestigious aspects of graphic communication is as pertinent today as ever it was!

Alan Marshall

And a film about tin printing…

Corporate film made by the Vereenigde Blikfabrieken (Association of Tin Manufacturers) and the Dordrecht-based Metaalwarenfabriek. Around 1900, the demand in the Netherlands for tin packaging began to increase, especially for decorated tins. The tin industry in the Netherlands was therefore becoming more and more sophisticated: the industrial production of tinplate printing became the norm, whereas manual tinsmithing was fading away. In this film we see two examples of industrial tin-printing in the 1930s. It shows how the famous tins made by the Droste chocolate company were produced.

Director: J.Th.A. van der Wal | Netherlands | 1930 | Production Company: unknown | Film from the collection of EYE (Amsterdam) – https://www.eyefilm.nl/en

[1] Alec Davis, ‘Towards a history of tin-printing’, in Journal of the Printing Historical Society, n° 8, London 1972, p. 54.

[2] Author notably of Packaging and print. The development of container and label design, Faber and Faber, 1967.

[3] Alec Davis, 1972, p. 54.