Alan Marshall, former director of the Musée de l’imprimerie et de la communication graphique (Lyon, France) and current chair of the AEPM.

In the early years of the AEPM, life was simple. As the name indicated, we were an association of European printing museums. Just that. Well… almost. Tucked in among the printing museums, large and small, were a few private collectors and collections, and even the odd heritage workshop. Not that that bothered us much, because collectors and workshops are printing museums’ natural partners. But it was only in 2012 that membership of the AEPM was ‘officially’ opened to non-museums. And it was only in 2014, that the decision became truly official with the registration of the AEPM as a not-for-profit association in Belgium.

The officialisation of the situation was not, however, without its own problems concerning, in particular, the name of the Association. If, in its brand new statutes, the AEPM was to be open not only to museums, but to anyone actively involved with printing heritage, including private individuals, should we keep ‘printing museums’ in the name, or should we change it to something else? In the end it was decided to keep the original name and to consider ‘printing museums’ as an identifiable focus, a kind of anchor which, by its continuity, would help in the development of the Association.

Though the AEPM has no reason to regret the decision to keep its name – membership has doubled since 2012 – the niggling question as to who we are never quite goes away and regularly comes up in informal discussions at our annual conference and elsewhere. So it is perhaps useful to consider for a moment some of the questions we raise when we talk about ‘printing museums’.

The main difficulty which arises whenever we talk about printing museums lies in deciding what actually constitutes a printing museum. Just what kind of organisations are we talking about?

The question might seem slightly odd for anyone who has already worked in, visited or otherwise run across a printing museum or two. But the closer we look, the less self-evident the answer becomes, for one of the most striking things about printing museums is that no two are the same. In addition, the more one looks into the subject the more apparent it becomes that printing museums are only the tip of the iceberg because, over the years, many other types of organisation have become involved in the conservation, study, exhibition and mediation of printing heritage: technical and industrial museums, libraries, archives and heritage workshops to name only a few. Likewise, printing museums do not restrict themselves the techniques of printing, but also display printed products such as books, newspapers, posters, advertising and packaging. So we necessarily have to include the products of printing within the definition of printing heritage. And if we include printed products, then we have to also include libraries and archives which are largely dedicated to the conservation and display of books, prints, newspapers and other printed documents, and which also occasionally acquire and display printing presses and other artefacts of the printing trades.

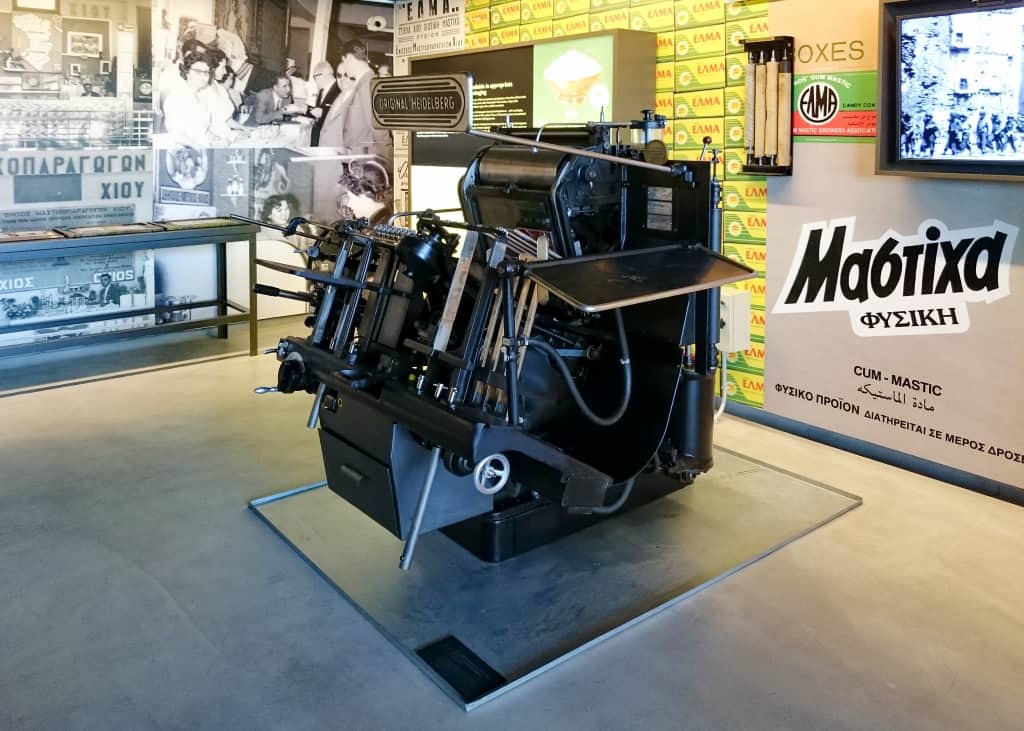

As for ‘printing museum’ in the strict sense of the term (if such a thing can be said to exist) it also covers a diversity of organisations of all shapes and sizes, working in related but often different fields, and pursuing a wide range of sometimes contradictory missions. And to complicate matters further, the frontier between printing museums and other museums which have an interest in printing is blurred by the fact that print has played a major role in virtually all aspects of social, economic and intellectual life since at least the early part of the nineteenth century, with the result that it has found its way – to a greater or lesser degree – into an extraordinary variety of museums and other heritage structures who do not a priori have a stake in printing history: for example, industrial museums who include a section on printing considered either as an important communications technology or as a natural extension of a more specialised productive activity.

Printing equipment and printed packaging and publicity displayed in the Mastic Museum on the Greek island of Chios. (Photo: AM))

The most easily identified printing museums are those which deal with the business of putting ink onto paper, the activity which comes first to most peoples’ minds when the word printing is used. When we think of a printing museum we generally think of printing presses and composing rooms with their drawers of lead type. The ancient crafts of wood-cutting and engraving might also come to mind because of their long history as a means of illustrating that noblest of printed products, the book. Industrial lithography if thought of at all (which it rarely is by non-specialists) also comes easily under the label ‘printing’, though it is much less widely or fully represented than letterpress printing in museums.

From there it is, in theory at least, but a short step to artistic print-making and book illustration with their panoply of subtle and often complex processes such as copperplate engraving, lithography (again, but artistic this time, rather than industrial) and, in the latter part of the twentieth century, silk-screen printing. However, printmaking – the printing of images primarily as a means of personal expression rather than as part of a commercial product such as an illustrated book or a poster (which does not of course preclude artistic expression) – is generally seen by the general public and by the artists themselves as belonging to the world of art rather than of industry. So, should museums devoted to printmaking be included under the general heading of printing museums?

And what of museums devoted primarily to printed products? Museums devoted to popular prints, playing cards or wallpaper sometimes think of themselves as printing museums because of they devote significant resources to explaining craft and industrial production processes of the past. Institutions devoted to books and book art, newspapers, posters and advertising and graphic design on the other hand do not spontaneously consider themselves to be part of the world of printing museums which in their eyes belongs to industrial and technological history.

And what of specialised sections of large generalist or technical museums devoted to printing or printed communication, and of the many heritage libraries, archives and university special collections who regularly display printed objects and evoke the techniques involved in their production? For technical and industrial museums, printing is an established speciality within their general remit, and they often maintain close links with recognised printing museums. Libraries, archives and university special collections on the other hand usually operate in quite different scientific, administrative and statutory environments which discourage any identification with printing museums as they are generally thought of.

Lumitype phototypesetting machine displayed in the printing section of the Musée national des arts et métiers, Paris. (Photo: Frédéric Bisson. Wikimedia.)

The list so far only covers organisations that exhibit a part of their collections on a permanent or temporary basis. But what of printing heritage materials which are seldom, if ever, put on public display? It is not unknown for printing museums to be closed for economic or administrative reasons and for their collections to be transferred to a larger museum or library, or to archives where they are put into storage with, or without, access for researchers. Likewise, many libraries, universities and even industrial and commercial firms hold major collections which are not open to the public and, in some cases are accessible only with difficulty for specialised researchers. Some university departments also have extensive heritage collections which are used primarily for teaching purposes and may only be made public when loaned to another institution on the occasion of a temporary exhibition. Given the size and historical importance of many of these collections, it is difficult to imagine them being excluded from discussion of the evolution of the process by which printing has become heritage. All the more so because some educational collections sometimes find themselves displayed almost incidentally in the corridors or other public spaces of their host institution, either as visual resources for students or to bring the collections to the attention of decision-makers within the institution.

Department of typography & graphic communication, University of Reading, United Kingdom. (Photo: AM.)

What, finally, of those workshops whose business it is to use printing techniques which have long ago disappeared from the industrial scene, and who very often explicitly claim the preservation and transmission of traditional skills and technical knowledge as part of their mission? Bibliographical presses are an obvious example, workshops in colleges and universities which offer arts and humanities students a practical insight into how texts and images have been reproduced for the last five hundred years. Many printmakers’ workshops and commercial or semi-commercial private presses also maintain active links with the world of printing heritage.

The Centre for the study of the book provides a common ground for scholars and librarians with shared interests in understanding, documenting and interpreting the intellectual and material history of the book. (Photo: AM)

And last but certainly not least, what about the private collections which are so often at the origin of the graphic heritage chain? Many of today’s institutional collections would not exist had it not been for the efforts of dedicated collectors who amassed and preserved what were at the time everyday objects considered to be of little of no cultural significance.

A printing museum by any other name

In practice, the seemingly narrow term ‘printing museum’ is commonly applied to a wide range of organisations with an equally wide range of motivations. The many museums for whom printing techniques, practices and products are the foundation of their collections, exhibits and activities often use it explicitly in their name, in whichever language applies: printing museum, musée de l’imprimerie, druckmuseum, drukkerij museum, museo della stampa, museo de la imprenta, museu da imprensa, etc. The term also covers a diversity of museums who spontaneously identify themselves as printing museums but who also have another, often stronger identity in a connected field such as papermaking, the book arts, popular imagery, newspapers and journalism.

As for the aims of printing museums – taking ‘printing museums’ either in the narrow or in a broader sense – they are profoundly influenced by the circumstances under which each organisation was set up, and they may well change over time. According to the centres of interest and aims of their founders or curators and the nature of their collections they can be very specialised or can cover broad subject areas, time spans and geographical areas, each museum positioning itself as best it can with respect to the many common themes which traverse graphic heritage, such as printing techniques, fine printing, graphic design, the impact of printing on society, etc. The very existence of many museums is the consequence of local history, their legitimacy and funding depending to a greater or lesser extent on the celebration of a local personality or tradition (such as Gutenberg, the manufacture of playing cards or popular imagery) or the contribution of printing to an emblematic local industry (packaging for the perfume industry, or textile printing for example).

In the light of the considerable variety of printing museums and the difficulties which can be encountered when trying to distinguish them from other types of organisation active in the field of printing heritage, is the term ‘printing museum’ in fact a useful category? Or might it not be more useful to consider printing museums as part of a larger category of museums, libraries and other organisations dealing with the history not only of printing but also of books, prints, newspapers, advertising, packaging, paper, graphic design and, more generally, communication? Printing is after all historically linked to papermaking and publishing as well as, in more recent times (i.e. for well over a century), to information processing and a host of industrial applications of which textile printing and printed circuits are the most obvious examples. Printing and publishing are also, from any point of view, the precursors and natural complement of the modern communication industries within which they have been progressively integrated over the past half century. Printing and digital media often share the same raw materials (texts and images) and cognitive and social functions. They also share similar preoccupations with their organisation, transmission and reception.

However, even for well-established printing museums the situation can be more complex than it seems at first sight. The celebrated Plantin-Moretus Museum in Antwerp, one of the oldest printing museums in Europe dating from 1877, no longer describes itself as such, preferring the term ‘historic house and monument’ or ‘Unesco heritage site’. Similarly, Lyons Printing Museum changed its name in 2014 to Musée de l’imprimerie et de la communication graphique in order to better reflect the full extent of its collections and the importance which graphic design has acquired over the last century and a half. In its change of name, the Lyons Printing Museum deliberately kept the familiar term musée de l’imprimerie in order to attenuate the probably rather less immediately comprehensible term communication graphique which nevertheless conveyed a much-needed sense of modernity to the establishment.

‘Printing museum’ remains a useful label however. Though the organisations having a stake in printing heritage often inhabit quite different worlds in scientific and administrative terms, and may assume or cultivate quite distinct identities, they regularly collaborate in the exchange of scientific information and objects from their collections, and even sometimes in the production of exhibitions and publications. More important still, they all have at least one thing in common: a desire to preserve and render intelligible what might broadly be called print culture and, directly or indirectly, to bring it to the attention of as broad an audience as possible.

Alan Marshall