This talk about the project to set up a British Virtual Printing Museum was given by Ben Weiner at the annual conference of the AEPM which was hosted by the Klingspor Museum and the Haus der Stadtgeschichte in Offenbach, 25 – 27 May 2023

Introduction

Good morning! My name is Ben Weiner, I live in London and I work as a software developer. I am currently the Secretary of the Printing Historical Society.

Originally, it was Dr Rachel Stenner who planned to be here presenting a talk about the Virtual Museum of Printing project in the UK. Rachel is the chair of the National Printing Heritage Committee which is a part of the Printing Historical Society. She is also chair of the executive committee that is guiding the Virtual Museum of Printing (VMP) project. Rachel is currently Senior Lecturer in English Literature 1350–1660 at the University of Sussex. Her connection to printing history comes through examining how writers depicted the printing trade and how members of the trade depicted themselves in writing. Unfortunately, work commitments have prevented Rachel from attending the conference. I hope that she is able to attend in the future and provide more news of this project. But today I am very happy to be here instead. I do not have Rachel’s knowledge of the project so please forgive me for errors of fact. I hope you will find my talk interesting despite this.

Print discovering its future is a topic that invites papers that also look forward. The title of this talk responds to that: ‘hopes and facts’. Of course when considering the future it is useful to look at the present. So in the first part of the talk I will set the project in its historical context and describe the current position. The Virtual Museum of Printing project looks forward to progress and perhaps one day completion, so I can address the hopes for the future too. In the second part of the talk I will describe the nature of the museum and the aspirations of the project. But first I would like to give some of my biography, and show how I came to be presenting this talk.

So what qualifies me to be here today?

I’m currently Hon. Secretary of the Printing Historical Society. This means I do my best to arrange our meetings, compile an agenda and take the minutes. I also get strange and interesting messages as my email address is the ‘catchall’ when people cannot find the appropriate person.

I grew up in Oxford, a small and rather unusual city about one hour from London. My family is very wordy, perhaps this is made worse because my dad is a lexicographer (a writer of dictionaries). I spent a lot of time drawing as a kid, including lots of lettering. Often I drew on the back of discarded ‘galley proofs’—long thin strips of paper from the Oxford English Dictionary which was hand-set at the University Press. I was introduced to the letterpress process as a teenager. I met Claire Bolton of the Alembic Press and had enormous fun in the school holidays treadling an Arab platen press and learning to set type. Like so many before me, I was captured by the experience: the feel of each piece of type in the hand, the calm absorption of setting lines in the composing stick, the steady rhythm of printing, the achievement of a stack of printed copies and the aesthetic satisfaction of the result.

I studied for a degree at the Department of Typography at Reading University. The unique undergraduate course placed a lot of emphasis on the historical roots of graphic design. We made two ‘European’ study trips: in fact one of them brought us here to Offenbach and the previous Haus der Stadtgeschichte in 1998. Following graduation I became a freelance designer and turned more and more towards the possibilities of the world wide web. I was lucky enough to attend some of the annual conferences of the Association Typographique Internationale (ATypI) where I met some of the true characters from the world of type design. At the same time I started to support St Bride Printing Library in London as a volunteer, helping to look after the Library’s web site. The Friends of St Bride arranged many events and conferences at that time, and I did much of the conference tech support. This was a great way to meet more type, print and design characters. Perhaps some are here today. I also helped set up a letterpress workshop at the library. The conferences, events and workshop represented a big change for St Bride. They were a significant increase in engagement with the graphic design community. St Bride Library was and is a crucial place in the spiritual world of typography and I was lucky to be involved.

I started a letterpress workshop in my garden shed, and when I moved to London the platen press gave way to a Vandercook proofing press in my kitchen. More recently, I joined the Printing Historical Society, which I will talk about in a moment. I did not intend to stand for the post of Secretary, but somehow that is what happened. And here I am today, with some relevant historical knowledge, some technical interest, and a rather emotional connection to the processes of printing.

So now let’s look at the origins of the Virtual Museum of Printing.

The background

In 2016 two printing heritage groups in the UK combined. If that had not happened, the VMP project would probably not be under way. These organisations were the Printing Historical Society and the National Printing Heritage Trust. To explain the origins of the VMP project, I will give a some of the history of each.

The Printing Historical Society was founded in 1964 by, among others, a librarian (James Mosley), an academic (Michael Twyman) and a journalist (James Moran). The librarian and the academic are still around today and both of them have contributed significantly to the literature of printing history in English. Mosley spent his career at St Bride Printing Library and Twyman founded the Department of Typography at Reading University, the place where I studied.

The interests of the founders included:

• typography, and the evolution, aesthetics and practicalities of type design;

• the influence of graphic techniques such as etching and lithography on the appearance of published images; and

• the processes of print production, the development of its machinery, and the growth of its industry.

The central aim of the Society was the production of a journal, which the original committee decided ‘should be printed in the best possible way’ . Perhaps it looks old-fashioned for its time, but then of course it was British, and it was produced by Oxford University Press. James Mosley’s preface to the first number, in 1965, set out the ambitions of the Society and the scope of its interests. In it Mosley noted the ‘regrettable’ absence of a ‘permanent home’ for the materials put together for ‘Printing and the mind of man’, a large exhibition displaying printing equipment in 1963. This was one of the motivating events that led to the PHS being founded. The professional concerns of people connected with the Society often included the preservation of the physical artifacts of printing, and this can be explained by the fact that it is easier to understand the end products if you can study the tools that made them. Among the seven essays in the first number of the Journal were included ‘The Garamond types of Christopher Plantin’ by Hendrik Vervliet and ‘Académisme et typographie: the making of the Romain du Roi’ by André Jammes, plus ‘The tinted Lithograph’ by Michael Twyman. These three all looked outside the United Kingdom, helping to establishing the Journal’s inclusive tastes and by extension the tastes of the PHS.

In time the Society became a charity and recognised that in addition to publishing material from printing historians of all kinds it could encourage them by offering grants to support their research—with the expectation that this support would lead to future articles. A grants programme was established and in recent years this has awarded a total of between £2 000 and £4 000 to around five or six applicants a year. The money is intended to support research by paying some of the incidental costs such as travel and reproduction fees. Since 2020, a prize for new scholarship offers further encouragement to people who are entering this field of research.

What motivates people to get involved? The Printing Historical Society has always been entirely made up of volunteers and all posts are honorary, in other words the work involved is unpaid. The contributions that members make reflect their professional interests in fields such as academia, archives and museums or the antiquarian book trade and their personal interests as book collectors, graphic designers or hobby printers, for example. What they share is an interest in aspects of printing history and a desire to share and extend that interest into the future.

In summary, the Printing Historical Society is an academically-minded, independent, group which studies aspects of the history of print. The Society fulfils its aims by publishing a journal. It seeks to nurture interest by offering grants that will support the kind of research which can be published in that journal. The Society is based in the United Kingdom but although it concentrates on Great Britain and Ireland its outlook is international.

National Printing Heritage Trust

The NPHT was started in 1990. I have searched in the PHS Bulletin around this date for a mention of the NPHT’s origin or an announcement of its foundation, but I have not discovered anything until 1992. Despite this, some of the people involved were prominent in the PHS at the time. Its chairman was Michael Twyman, also a PHS founder.

The NPHT was a grant-giving organisation from the beginning. Its aims, as laid out in a prospectus from around 1994, are tightly concentrated on the techniques and equipment, in other words the production aspects of printing:

- assisting museums to buy items related to printing;

- encourage external projects to relocate, restore or preserve equipment and archives;

- if funds become available, purchasing or rental of premises where equipment can be stored and renovated;

- if funds become available, financing wholly or partly a national museum of printing.

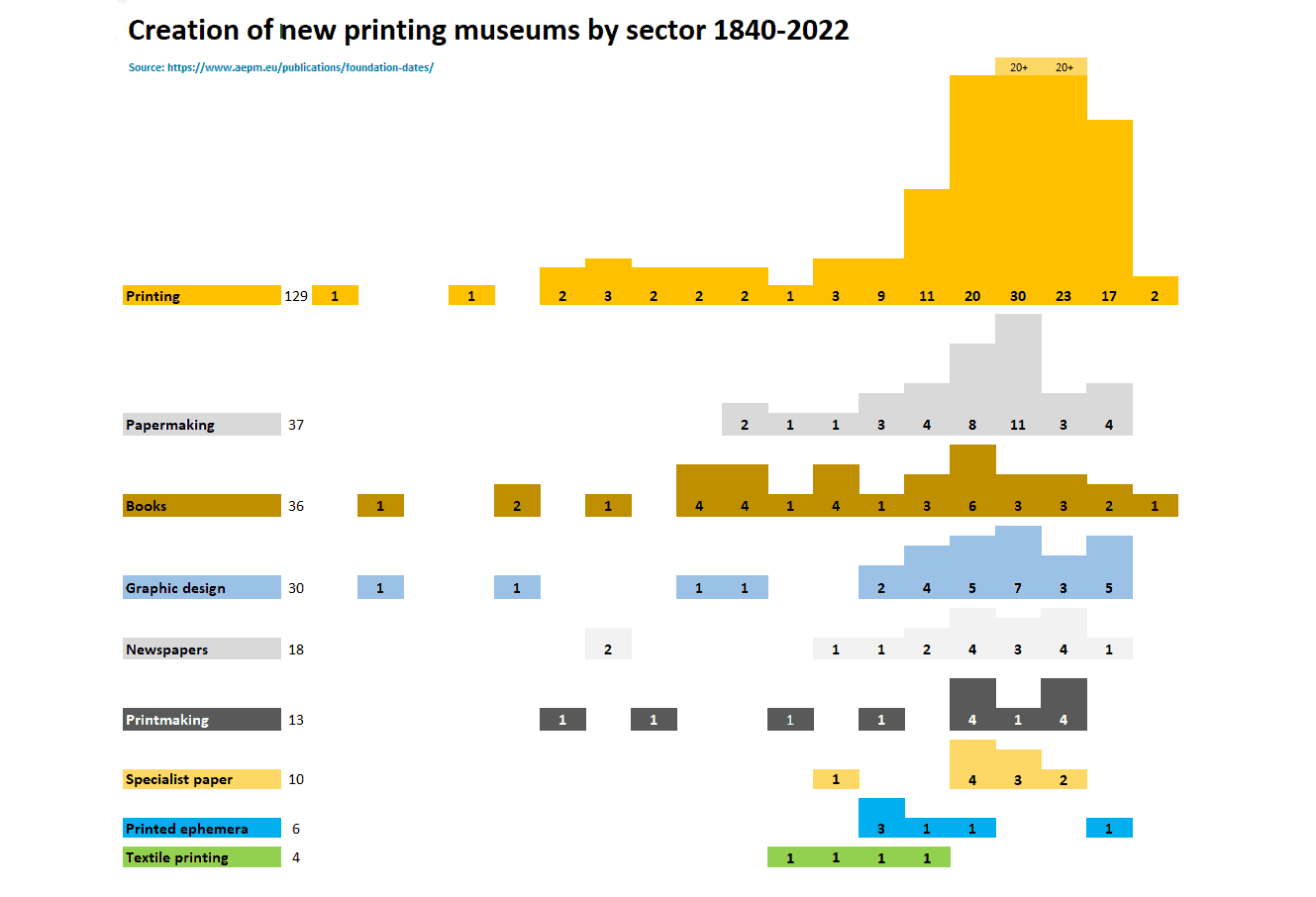

These aims and the NPHT’s foundation date of 1990 remind me of Alan Marshall’s talk to this conference a year ago in Malesherbes: the image on the screen behind him while he spoke was a timeline showing the numbers of printing museums and collections established per year over a period from 1840 to 2022. It was an effective graphic. In the context of Atelier-musée de l’imprimerie (A-MI), our host for that event, the data seemed to offer a memento mori, a reminder that the trend to create printing museums is very much downwards. But of course A-MI’s existence challenges the idea that this decline is terminal. Today, I would like to borrow the chart to offer a post-rationalisation of the origins of the NPHT. This is my personal interpretation of the situation.

As we saw, 25 years earlier James Mosley had written of his regret that there was no ‘permanent home’ for outdated printing equipment. But the PHS was concerned with publishing research rather than preservation. As the Librarian at St Bride Printing Library, Mosley himself had rescued large amounts of printing equipment since the late 1950s. But it disappeared into the Library, in truth an archive, and was far out of sight of the public. Access to this collection depended on knowledge of the Library and a visit to London. Its catalogue was not public.

The situation around the country remained basically the same as it had been then. Regional museums might display artifacts related to local printers, perhaps laid out to replicate a letterpress workshop. At the national Science Museum in South Kensington, London, there was a printing gallery which featured a Monotype caster on a rotating pedestal . But there was no national museum for printing.

Alan Marshall’s chart shows us that 1990 is in the peak of the period where new museums for printing were being established. So it is likely that the same factors which drove the creation of new museums worldwide were strongly influencing the desire for a national museum in the UK.

The NPHT’s prospectus leaflet shows us that unlike the PHS it was actively supporting people in their efforts at preservation. It had given ‘financial help as well as practical assistance to a number of museums’. Although this would not help to save up for a future national museum, it was an investment that would encourage professionals in museums and archives and therefore perhaps inspire more interest from future generations.

In 1997 the NPHT published its Inventory of historic printing items held by museums in the United Kingdom. This document was issued again in 2000 as the Directory of historic printing items held in the United Kingdom and Ireland. Tony Smith, who joined the NPHT’s advisory committee in 1994, calls it a ‘remarkable achievement’ and NPHT’s later publicity claimed that it ‘sets a standard for similar publications in other subject fields’.

The publication of such a directory was a significant step beyond the original aims. Its intention was to open up all the collections of printing material around the UK and Ireland, greatly reducing the difficulty that individuals would have in carrying out research tasks. It is something we are constantly forgetting, but before the world wide web the process of uncovering information was much more a matter of chance than of brute force. A letter asking for information, published in the PHS’ Newsletter or later Bulletin, had to await the publication date, up to three months away. It might go unanswered. Without online catalogues, archive enquiries were handled by staff case by case rather than in real time by the researcher. A directory would cut much of this time and allow enquiries to go straight to the appropriate person or organisation.

In fact, as a more recent example of NPHT publicity from around 2000 reminds us, the internet was closing in fast. After describing the Directory, this flyer states: ‘it is intended to update its contents, and to make it accessible via the internet’. The Directory was converted to a spreadsheet database, but despite several attempts it was never put online. This was a source of disappointment and frustration for those involved in collecting and processing the information.

Trust becomes Committee

The Trust continued its independent existence for 25 years until 2016. In that year, faced with the resignation of the President and the Treasurer and with a reduction in the number of trustees, it seemed inevitable that it would have to close. I mentioned that several of the people involved in founding the NPHT were also closely involved with the PHS. This was also true in 2016. A decision was made to unite the two organisations. This meant the NPHT’s work could continue without needing officers or trustees. The money it held was placed in a dedicated account by the PHS. The new National Printing Heritage Committee kept the aims of the NPHT. Its dedicated fund allowed it to perform the same grant-giving that it had when independent. Administration costs were reduced. At the time when the committee was formed, the core work of the Trust was listed as ‘fund-raising, grant-giving, lobbying, promotional and record-keeping’.

Virtual Museum of Printing

At the date that the NPHT and the PHS came together, the Trust’s aim of financing wholly or partly a national museum of printing had not been realised. In fact, it seemed to be no closer than it had ever been. As mentioned, the NPHT Directory was not up to date. No new editions had been published, despite intentions to do so. But in 2020 the committee’s chair, Paul Nash, was able to report to the PHS annual general meeting that ‘although there was no immediate prospect of a National Printing Museum being established in bricks and mortar, the NPHC is now considering a move towards its ultimate goal by helping to establish a virtual national museum, to allow museum curators and collectors to make their collections visible and comprehensible through a combined virtual display’. This announcement marked the start of the Virtual Museum of Printing. Paul’s quite modest report rather masks the ambition of the project, which in its own words ‘will be a virtual museum collective with the objective to bring as much of the nation’s printing-historical resources as possible together in one virtual site.’

Green shoots

What had led to this new initiative? As Lee Hale, chair of the Virtual Museum of Printing’s executive committee told me, it is a story that takes us away from London. Lee is the Head of Winterbourne House and Garden in Edgbaston, a leafy suburb of Birmingham two hours away from the capital. Winterbourne is owned by the University of Birmingham. It served as the University’s botanic garden and extramural department, and this connection with the community has been greatly expanded in the last two decades with informal short courses open to the public. Originally these focused on gardening and craft. When a collection of printing equipment located in another University building nearby came under threat, Winterbourne gave it a new home and added printing subjects to the courses on offer.

Another Birmingham initiative, the Centre for Printing History and Culture, came to adopt Winterbourne as a home. CPHC members included several people connected to the PHS and NPHC. In this atmosphere, where there was support for printing history and public engagement, an informal idea for a virtual museum of printing came to life.

Project partners

With such ambitious aims, the project goes beyond the capabilities of the NPHC acting alone. Instead the VMP project draws on the resources of several project partners, rather than being solely the responsibility of the NPHC. The current partners are the PHS, the University of Sussex, the Centre for Printing History and Culture, Birmingham City University, the University of Birmingham, and Winterbourne House and Garden. Representatives of each of the partners agree on governance and finance, provide access to their own networks, and of course encourage one another. An increase in the interaction of groups who share an interest in the subject matter has its own immediate benefit for all of them. The VMP’s project plan sees this network strengthening as a strategic goal of its own.

The original plan envisaged translating, as far as possible, the capabilities of a museum into a web site. The NPHC itself has no collections and so this museum would display items in collections held by other organisations around the UK. The contributors would select these items which would have interpretive text, as in a physical museum, giving their origin and explaining their significance. They might be scanned documents, photographs of artifacts, 3D models or videos of processes. Just as a physical museum needs to support its visitors’ interest and learning with coherent narratives, so this virtual museum should be coherent. Because of this, the selection of items might need to be curated by the VMP project rather than left to the contributors.

The Virtual Museum was planned to be launched in stages, allowing experience at each stage to inform the next. An important task was to get the agreement of a number of suitable collections to contribute to the initial version. The project now has a list of around 20 collections that are substantial enough to be initial contributors. The original plan for the first launch was to use the material from these collections to form the Museum’s own initial ‘display collection’. The success of this would be the spur to encourage more collaborators to join the project.

Although it was not fully up to date, the NHPT’s Directory represented a source of information about possible collections to approach. As we know, updating the Directory has been an ambition of the NPHT and the NPHC for many years. The Directory can be seen now as an aspect of the virtual museum—a gazetteer derived from the content that has been contributed. Visitors searching for a particular artifact will see immediately which organisation holds it, and can use this as the basis for making contact with them, just as the Directory’s creators envisaged. The virtual museum could also be seen as turning the Directory into an immersive catalogue for all the contributing collections.

In the project’s strategic plan, there is an aspiration to provide online interactive activities such as workshops and demonstrations just as can be offered by physical museums. This will connect the project both to the professional side of printing and to the contemporary art and craft side, which is now sufficiently well established to have a history of its own.

An ambitious project

I think the VMP is a remarkable step for the Printing Historical Society to take. This is for several reasons. Firstly, the need to build relationships with contributors. As a publisher rather than owner of its own collections, the VMP must get each contributor’s agreement to share their data with the project.

The VMP project understands that it must build and nurture relationships with the custodians of each collection, because the selection and display of items will require careful collaboration to display and describe them rather than simply uploading files. Those contributors will need support to bring their holdings into the virtual museum. That means help in documenting the artifacts with photos, videos or 3D models along with copywriting and editorial assistance. And this work has to be fitted into budgets and timetables that are often not generous.

Secondly, it engages with the public. I am speaking to an audience which is familiar with the demands of engaging with the public. But this is not something that the project’s owner, the Printing Historical Society, has ever sought to do. Certainly, it has organised events. But participants will generally be well-informed, having already gained specialist knowledge. Museums expect a very different audience: they welcome all comers, engage with all interested visitors and seek to provide ways to explain why the treasures they hold are significant and special.

When the Directory was created, the National Printing Heritage Trust did not need to worry about interpreting the collections. It was enough to share knowledge of their existence. The VMP will build considerably on the foundation provided by the Directory. Writing or talking about anything for an audience that does not have already have relevant knowledge takes extra effort. Selecting items that will inspire the public will require curatorial skill. The project’s strategic plan discusses the importance of engaging with everybody: considering different backgrounds, experience, age groups, abilities and interests.

A third point concerns resources. The Printing Historical Society is not a wealthy organisation and it does not have a very large membership. Alone it could not contemplate such a project. Again I must apologise that I do not have details of the commitments made by the project partners, but my understanding is that they will contribute time and expertise in the early stages rather than providing funding or long-term support.

The project must generate enough interest and excitement to gain significant financial support from external sources for its future ambitions. It must retain the engagement of the project partners so that they can continue to guide it. It must find a way to carry out the background administrative tasks necessary to keep the project active. With good connections in the world of heritage funding this may be an easier task than it would have been for a group built solely around the PHS and the NPHT.

First site launch

The initial vision for the museum was to exhibit items from each of the initial contributing collections with interpretive text giving their origin and explaining their significance. The VMP project got started around about the time of the COVID-19 pandemic, with all the upheaval that brought about. As we all know well, this disrupted work, disrupted spare time, disrupted budgets and led people and organisations everywhere to see things differently. And alongside this, the practicalities of starting a project with involvement from several partners have pushed the launch date back around 18 months.

So, to bring things up to date, as Rachel Stenner told me, ‘the barriers in our way – capacity and finance – have helped to show us the approach to take. The first phase of this project is about building capacity and awareness, so that we can go on to do more’. What the project now proposes for the first launch is to publish a list of the contributing collection holders. Each collection holder will have a profile and a single sample object from their collections. The list of collections has value in its own right as a gazetteer: just as with the original Directory, publishing the list contributes to improving public access to the collections.

When it launches, hopefully in autumn or winter 2023, the museum will acknowledge that it is at an early stage and share its vision of future stages. The first launch will give everyone a chance to find out more about the contributions that the VMP can make. The printing community on one side and the museums and archives on the other have different needs and expectations, and the experience gained at this stage can be used to balance these. The project partners hope that the emergence of the Museum will encourage more discussion between the two groups. The insights into what audiences most appreciate about it, and most want to take from it, will provide a good basis to consider the next steps in its development.

Conclusion

The title of this conference is ‘Print rediscovering its future’. If the VMP project goes well, then it could represent a rediscovery of interest in printing by the public. It will also be something new for the world of museums. Until very recently, creating a museum with no holdings of its own and no physical presence would have seemed very strange. It directly challenges the idea of a museum as something anchored to a location, physically framing its collections and inheriting much from the qualities of its surroundings.

The VMP will have no surroundings, as well as having no café and no weather outside. There will be no staff to welcome visitors and no tours with a guide. There will be instant access to any artifact but no opportunity to smell or touch anything. The experience will take place in the realm of the mind and will not have physical resonance. But if the museum can add sufficient depth and context to the items it displays, it will still be an immersive experience. As we all know, the internet doesn’t have opening hours and it is easily possible to spend much more time than expected on a web site that you just happen to visit. Behind the scenes there could be gains for the community as project partners work together to bring the collections to the museum.

So this will be a very different kind of printing museum. But it could also be a very valuable contribution to the future of printing history.

Ben Weiner