Li Portenlänger (www.lithos-jura.de)

The invention of lithography and the Solnhofen quarries

Text of a paper given by Li Portenlänger at the conference of the Association of European printing museums From stone to chip: Alois Senefelder and the invention of printing in an international context, Nederlands Steendrukmuseum, Valkenswaard, The Netherlands, 3-5 November 2016. Li Portenlänger, Eichstätt, copyright. Translated by Andreas Weiland, Enger.

The mining area of the best lithographic limestone found worldwide is about 20 kilometers away from the place where I live in Bavaria. This region with its deposits of Solnhofen limestone plates, so-called Solnhofener Plattenkalk, has an extension of about 40 kilometers. Eichstätt is a university town, a diocesan town, and it is also noteworthy for its baroque architecture that dominates the entire historic center.

In 1998, I established the Eichstätt Lithography Workshop (Lithographie-Werkstatt Eichstätt) in cooperation with the city. Internationally renowned artists primarily engaged in lithographic printing are invited as guests or artists in residence. It is in this context that the Eichstätt collection of lithographic prints originated. Preserved in the university library, it is publicly accessible.

When Alois Senefelder invented lithography, he was living in Ingolstadt (25 km distant) for the purpose of further studies. It was here that he was granted a scholarship by the Electoral Princess of Munich. While studying law and economics (then referred to as Cameralwissenschaft or administrative science), he also sought to discover a new or more simple technique for reproducing texts. In 1796 he found this to be possible by etching stones. The process he found was based on the traditional techniques used in the printing of copper engravings. His main interest was focused on the theatre and poetry however, and he hoped to be able to print his own writings. Thus he continued to experiment and in 1798, invented planography, or ‘chemical printing’ as he called it, what we know as lithography. In this context, he developed a new reproduction technique.

At the time when lithographic printing was invented, Solnhofen lime stones were a very affordable and easily available material. They were used as floor panels in churches and secular buildings. The traditional rural houses were also built with lime stone, their roof being covered with thin limestone plates.

How did all these stone plates with their different thickness originate?

About 150 million years ago, the Earth presented an appearance that was very different from today. The large Southern Gondwana consisted of a land mass that comprised South America, Africa, Madagascar and India, Antarctica and Australia. North America, Europe and most of Asia formed the northern continental plate, Laurasia. Between Gondwana and North America, the Midatlantic had formed. Its extension, reaching eastward as far as today’s China, was the Thetys Sea. Thetys is the name of the Greek goddess of the Sea. What today is Europe, consisted of an archipelago of relatively large islands, separated from each other by shallow straits and inlets. At the margin of the European shelf, an elongated carbonate platform developed. It consisted of microbial sponge and coral reefs, and was also partly formed by limesands. In the depressions, the so-called basins, limestone plates formed.

In central Europe during the Late Jurassic Period, the elongated carbonate platform formed the limit of the European continental shelf in the South East towards the Pennine Ocean. Towards the Northwest there was the large Rhenish Island with the London-Brabant Massif and the mid-German Rise, towards the East the Bohemian Islands. The Southern Frankonian Alp was the region where the Solnhofen limestone was deposited.

The scenario of the origin of genesis of Plattenkalke: in the North West was situated the Rhenish Island. Higher mounds under the sea were formed by microbial mats and sponges. Situated between these mounds, stratified limestone formed the ground of the basins. This is how the Plattenkalke came into being. In the deeper zone, close to the bottom of the sea, hypersaline and thus hostile waters concentrated, whereas the upper zone permitted life. On the carbonate platform in the further Southeast, fine lime mud was deposited. Tropical storms stirred this up and transported it into the basins. Living animals were stirred up as well and swept into the hypersaline bottom zone, where they died immediately and were covered by the fine lime mud. This formed the lithographic limestone layers. Every layer represents a storm event.

Transmission electronic microscopy reveals the homogeneity, regularity and density of lithographic limestone. The finely grained structure of the lithographic limestone is caused either by bio-erosion, for example decomposed calcareous particles of coral reefs, and decomposed plankton particles, or bacterial and algal precipitation. It was this finely grained, homogeneous, dense material, which absorbs fat and water in equal measure, that made Alois Senefelder’s discovery of lithographic printing possible.

Lithographic stone deposits

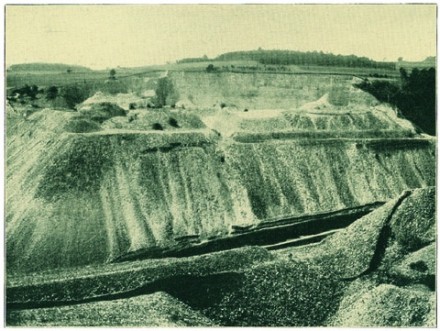

The old Horstberg quarry features the thick layers that produce the valuable gray-blue lithographic stones. Starting from the top, the quarry workers advanced slowly through the unwanted soil and stone layers that ended up on slag heaps in order to get to the coveted layers known locally as flinzes. Tunnels were dug in order to find out whether it was worthwhile to advance still further. The ‘Horstberg’ Mountain, as a quarry location, exemplifies a development that mirrors the context of limestone-mining. A photograph taken in the 1930s and the current state of slag heaps are good indications of the enormous amount of stone that was mined here.

The quarry was opened up in 1668. Initially the stones were destined to be used as floor coverings of the kind found in the region’s churches and abbeys of the period. The larger, thick stone plates were used for stone-made stairs and door frames. At the end of the 17th century, the quarry was abandoned. Round about 1830, the growing demand for high quality lithographic stone led to a feverish search for exploitable deposits. A merchant, Franz Heinrich Horst of Strasbourg on the Rhine who was marketing lithographic stones, applied for a concession that would enable him to exploit the old quarry location. The lithographic stones mined here were transported overland to riverboats in Strasbourg to be shipped downstream to other European countries, and even to Great Britain and overseas destinations. At the time, there were lengthy quarrels and discussions, as Mr. Horst was the first stranger in the region who sought to buy a quarry, and the quarry site he finally acquired belonged to several owners. In the end he succeeded in acquiring the location.

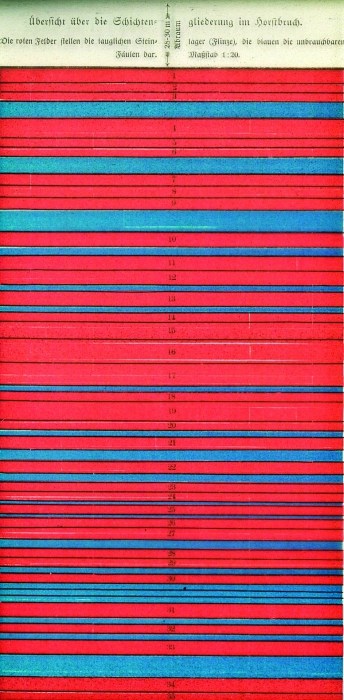

A characteristic survey of the series of layers in the Horstbruch area was done in 1928. Every layer was given a name with the density of layers varying between 1 inch and 6 ½ inches (3 to 17 centimetres). The layers called ‘Flinze’ were suitable for several purposes. The thinnest were used for roofs. The layers of marly or ‘foul’ stones could be used neither as lithographic stones nor as floor covering or for other purposes. The usable layers were formed in brief periods of time. Scientists assume that this happened within a few days. Marly layers point to longer periods of formation when stones formed on the bottom of the basins. The ‘Flinze’ could be differentiated by thickness. In the Solnhofen area, the sequence of layers could be around 40 meters whereas in the Eichstätt area, 20 kilometers away, the depth of sediment stones amounts to between 5 and 15 meters.

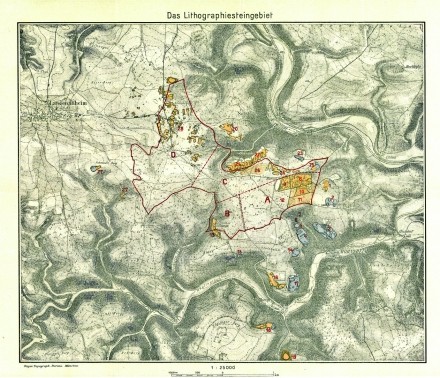

Let us now look at a topographical map. The lines depicting meandering courses of valleys helped flesh out three-dimensional mountain regions. The patches marked yellow and blue indicate stone quarries. Yellow indicates deposits of yellow limestone. Blue indicates deposits of much harder gray and blue stones. In the upper reaches of the valley formed by the Altmuehl river, we find the village of Solnhofen. Moernsheim, which we will see in the film Lithographen Schiefer by Hubert Schonger (see below), is situated in a side valley. Positioned centrally between these two locations, the Maxberg Mountain rises in the landscape. The company located at this mountain is still producing lithographic stones today. A bluestone quarry marks the site of the so-called Horstberg Mountain. Further up there are the yellowstone desposits of the Langenaltheimer Haardt. Solnhofen was to lend its name to the entirety of the regional geological formation. A railroad reached Solnhofen very early on, providing a traffic link to the world.

In order to provide an idea of the quantitative dimensions of lithographic stone mining, the storage facility for historical items of Bavaria’s Land Survey Office in Munich may give an insight. A lithographic printing department was established there in 1808, with Senefelder as its director as of 1809. In the wake of the political transformations that occurred around the turn of the century, exact land surveys were undertaken. A total of 26,634 (twenty-six thousand six hundred and thirty four) lithographic stones carrying the images of drawn maps of the whole of Bavaria are still preserved in this ‘stone library’.

In 1935, still in the heyday of lithography, five stones were produced measuring 135 x 175 centimeters. They were shipped to London and used for the printing of nautical maps. The man who participated in the production of these large lithographic stones was a stone worker just like his father and grandfather. I still knew his son personally. He also produced lithographic stones. If, at the beginning of the 20th century, every firm of the Solnhofen – Moernsheim region was engaged in producing lithographic stones, today only one company remains active in this industry, operating on the Maxberg Mountain. A single worker, truly a specialist, today finishes all the lithographic stones that are shipped from the Maxberg to customers the world over.

The storage facility for lithographic stones of the company exploiting the Maxberg still has a stock of partly finished gray stones of the best quality that were mined in old, now abandoned quarries. Final finishing of a stone by the company involves:

- working it with the schlageisen, a beating iron tool;

- rounding off the edges;

- filing the stone’s corners;

- working the sides of the stone plate with a bush hammer (Stockhammer);

- checking of the finished lithographic stone with a moist sponge.

Thin stone plates of the best quality are glued together these days using epoxy resin.

About the stone and lithography

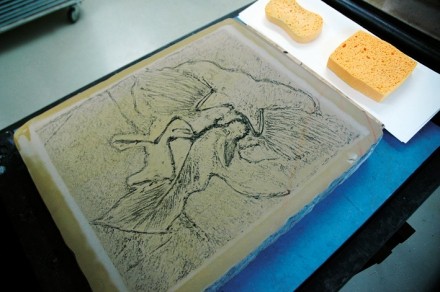

The Archaeopteryx lithographica is especially famous; it is almost an icon among fossilized animals discovered in Solnhofen limestone. This animal forms the link between reptiles and birds. The theory of evolution sees birds as a further development of two-legged dinos. The epithet ‘lithographica’ points to the relation between the fossil find and the motivation for mining limestone. It was the invention of lithography which caused a huge increase in the quantity of limestone mined. As a side-effect many fossils were discovered.

The Rhizostomites lithographicus-Haeckel, is a jellyfish fossil which allows us to appreciate the fineness of Solnhofen limestone, the soft parts of this animal having been fully reproduced in the ossification. The second part of the name of this fossil again emphasizes the relation with lithography. The demand for lithographic stone exerted by the market was the decisive factor that determined the quantity of fossil finds. The considerable quality of especially fine and homogeneous material in demand (so-called ‘litho quality’, as the mining company active on the Maxberg mountain calls it) determined the context.

The name of the fossilized jellyfish points to yet another connection – with Ernst Haeckel – an enthusiastic biologist of the 19th century. His book Kunstformen der Natur (Art forms of nature) was intended to show the wonders of the world in one hundred pages. Haeckel supported the theory of evolution developed by Charles Darwin and wrote monographies on a number of species. For the publication of his research he needed and found a lithographer who rendered the research results in a way that proved to be very much in the biologist’s spirit when the task of drawing and printing was accomplished. This lithographer was Adolf Glitsch (1852-1911).

During the heyday of lithography the company known as Solnhofener Aktienverein auf dem Maxberg had branch offices in Milano, London, St. Petersburg, New York. Business contracts concerning lithographic stones were concluded with customers around the globe. A postcard printed for public relations purposes shows a typical lithographic stone from Bavaria.

Lithographically printed money printed by the Solnhofen municipality in 1921 refers to the significance of lithography with regard to the entire region. The face of the 50 Pfennig note shows the sculpture of Alois Senefelder placed in Solnhofen. The back of the 1 Mark note gives the view to the basilica of the founder of Solnhofen, the Saint Sola.

Lithography as a new technique of reproducing images entered all spheres of everyday life. The image gained more and more importance with respect to the transmission of information. It was not only for industrially produced prints that new stone material was needed again and again. From the very beginning, artists used the possibilities of lithography and relied on professional lithographers for the reproduction of their individual artprints or folios.

Since the early 1960s, vocational training of lithographers is a thing of the past in Germany. With the result that the situation of lithographic printing studios changed totally. In the age of digital transmission of information, artists are the only people who use this technique that was widely applied during more than 200 years and that developed in many ways in the course of its application. Today there exists a globally networked fold of enthusiasts who partially master this special technique and who use it in the context of their art. In 2016 the Eichstätt Lithography Workshop invited as guest lithographer the artist Walter Dohmen. He made a frottage of the Archaeopteryx Lithographica and transfered it onto stone. The genius loci is leading us as a mediator through millions of years of the planet’s history.

______

I would like to thank Dr. Günter Viohl, Eichstätt, geologist, paleontologist.

In context I refer to the book: Solnhofen. Ein Fenster in die Jurazeit 1 + 2, Verlag Dr. Friedrich Pfeil, München, ISBN 978-3-89937-195-6. Lithographie.

(PORTENLÄNGER) (p. 28 – 37), Die Lithographie.

(PORTENLÄNGER) (p. 38 – 40), Die Lithographie-Werkstatt Eichstätt.

Lithographen-Schiefer

Lithographen-Schiefer, by Hubert Schonger (With the kind permission of PeriscopeFilm.com)

This film is unfortunately no longer available online.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MeRfspn67j8

This film, made by Hubert Schonger, shows the landscape of the village of Moernsheim, round about the year 1935. The Maxberg Mountain is situated on opposite side of this valley, and was named after the first king of Bavaria, Maximilian I. Joseph. Here above Moernsheim are the most precious blue stone deposits.

The film shows:

- the geological formation of layers and the way they appear in the quarry

- the railway system used to transport the mined stones

- workers mining stones

- the expert assessing the purity of the stone by listening to its sound

- cleaning a big stone from layers of marl

- the partition of a large slab of limestone into big pieces

- the individual stone layers of the big slab being separated

- a wooden frame used to determine the size

- stones being transported from the quarry to the workshop

- disposal of stone debris or waste material

- the lithographic stone being worked or made ready: washing, grinding and graining, and finally worked as a specific lithographic stone format

- the artist’s drawing already prepared is printed on a large-format lithographic press.